EXECUTIVE BRIEFING

Leadership Practices for Competitive Performance and Adaptive Renewal

In the world of leadership competitive performance and how to improve and sustain it is a topic discussed frequently.

Over the past few years, organizational and personal renewal have risen to become very hot topics. And yet there remains some misunderstanding about how managers can contribute to align competitive performance with adaptive renewal, what it is and what it entails.

This CLD Executive Briefing focuses on leadership practices that align Competitive Performance with Adaptive Renewal.

Managerial roles come with responsibilities to engage people and teams, enabling them to use their talents effectively and willingly to achieve organizational goals. Managerial leaders are also tasked with supporting the process of renewal – continuous learning and development, improving and changing themselves and others to drive forward organizational and personal adaptability and renewal.

High performance working together with continuous improvement and renewal are the two pivotal dimensions of managerial leadership roles that deliver current and sustained competitive advantage. Organizations and managers that embed adaptive learning and renewal practices throughout their day to day operations are more likely to survive and thrive, consistently delivering high performance, profitably.

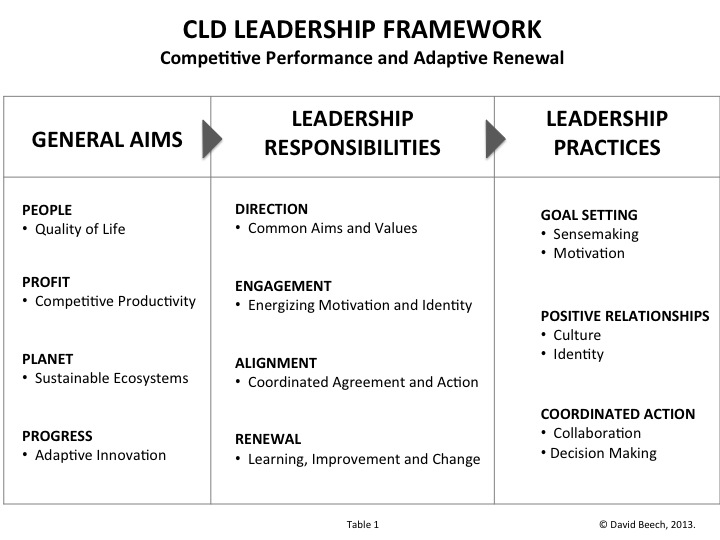

Overall effective managers are masters of establishing direction, engagement, alignment, and renewal – DEAR. This executive briefing focuses on six fundamental categories of leadership practice, which in concert enable DEAR and achieve locally relevant quadruple bottom line aims and outcomes for people, profit, planet, and progress.

Section One provides an overview of CLD’s leadership framework. This practical framework – see Table 1 below – is an original synthesis of robust leadership research findings¹. Section two defines each of six categories of leadership practice and provides examples of specific practices for each category for use by team leaders, managers, and executives. Section three outlines how leadership is informed by the general action processes of cooperative and competitive relationships in the implementation and innovation tasks of competitive performance and adaptive renewal.

1 An Overview of CLD’s Leadership Framework

CLD’s ongoing applied leadership research began over 15 years ago. The CLD leadership framework represents our evidence based understanding, knowledge, and insights on leadership and leadership development. Its focus is competitive performance and adaptive renewal.

This research has been applied in highly customised evidence based leadership and organization development programmes with over 1,500 senior executives and middle managers in dozens of organizations worldwide.

We know a great deal about the general aims of leadership and organizing for results, about the functional responsibilities of managerial leaders, and about the practices which engage people in action for performance and renewal in constantly changing and often ferociously competitive circumstances.

Specifically, a person who influences others to engage in action for common aims and mutual benefits in evolving circumstances is a leader.

Most of us have the capacity to influence others in relation to a common goal in certain circumstances. However, there is huge variation in the scale and scope of our impact. For instance, the ideas and influence of Mahatma Ghandi, Martin Luther King, and Ang Sang Suu Kyi continue to inspire and impact the lives of millions of people around the world. However, everyday hundreds of millions of front line supervisors and managers in offices, factories, workshops, distribution centres, call centres, and retail outlets exercise the kind of practical leadership influence that contributes in an infinite variety of ways in engaging people in common aims to achieve a range of locally relevant outcomes for a quadruple bottom line of people, profit, planet, and progress.

There is no one best way to lead. Each person is the author of their activities and identity, including their leadership contributions, in their way in their circumstances. Nonetheless, there is an underlying structure to leadership in terms of general aims, functional responsibilities, and categories of leadership practice. In particular, there is a substantial body of research findings on the leadership practices that enable fulfilment of DEAR responsibilities in order to realise quadruple bottom line (QBL) aims and outcomes for competitive performance and adaptive renewal.

General QBL Leadership Aims

The foundation for a decent quality of life for more and more people around the world is competitive productivity in the production of goods and services at a profit. In particular, the creative competition of capitalism relentlessly drives costs down and simultaneously catalyses adaptive innovations in products, processes, and business models, constantly enabling further improvements in quality of life.

The call for responsible leadership is urgent and compelling, since achieving sustainable prosperity for an expanding world population of over 7bn people demands an infinite variety of specific and locally appropriate quadruple bottom line aims and outcomes. QBL aims and outcomes cannot be achieved in isolation; they require the support of innovations in institutional and governance arrangements to progress the achievement of sustainable ecosystems across the planet, whilst also extending the enjoyment of human rights to individuals and their interdependent communities everywhere.

QBL aims and outcomes require effective contributions across a range of contexts at all levels of leadership: cabinet office and boardroom action on institutional arrangements and legitimacy; executive action on strategic competitive position; operational management crafting and updating of systems and processes for implementing strategy; and frontline delivery by managers, supervisors, team leaders and their work associates. Sustainable success encompasses shared direction, employee engagement, and coordinated alignment of information, decisions, and activities, together with achieving continuous renewal and innovation. These are the DEAR responsibilities of leadership: direction, engagement, alignment, and renewal

Leadership Practices and DEAR Responsibilities

Cumulative findings in leadership and organization science from the 1930s onwards identify broad categories of interrelated leadership practice. These categories of leadership practice drive fulfilment of DEAR leadership responsibilities across all contexts and levels of leadership.

There are six broad and interrelated categories of leadership practice and each is supported by a substantial body of research findings²:

- Sensemaking: ensure everyone understands the situation

- Motivation: establish energizing reasons for action

- Culture: promote shared beliefs, values, and norms

- Identity: promote group membership, attachment, and cohesion

- Collaboration: enable people to work together to the same end

- Decision Making: involve people in decisions that affect them

Broadly, sensemaking and motivation practices are of particular importance in goal setting; culture and identity practices are decisive in promoting positive group and organizational relationships; and collaboration and decision making practices are essential for the coordinated action through which common aims and mutual benefits in evolving circumstances are realized.

However, and crucially, in fulfilling DEAR responsibilities the most effective leaders integrate reflective learning and renewal activities relevant to each category of leadership practice.

2 Six Categories of Leadership Practice

In combination the six categories of leadership practice drive fulfilment of DEAR leadership responsibilities and thereby enable achievement of a locally relevant configuration of QBL aims and outcomes. Further, the six categories of leadership practice can be organized into the three domains of goal setting, positive relationships, and coordinated action.

GOAL SETTING DOMAIN: Sensemaking and Motivation Leadership Practices

We are all naturally goal oriented; and, our beliefs and desires inform our goal directed action providing energizing reasons for action.

Today’s increasingly competitive and turbulent commercial environment demands that all teams and their leaders focus on performance and continuous improvement. Leaders who master the interconnected goal setting practices of sensemaking and motivation will have a head start.

Use the statements below to review how frequently you observe these practices in your situation. For example, a team can score their manager or themselves on a scale ranging from almost never (scoring one), to almost always (scoring five):

Sensemaking: ensure everyone understands the situation

- Clear goals and values are communicated

- Shared expectations are established

- Regular and constructive feedback is given

Motivation: establish energizing reasons for action

- Individuals can use their knowledge & skills

- Individuals can exercise initiative & discretion

- Individuals trust each other

- Individuals embrace an obligation to add value

Higher levels of performance are achieved when shared goals, values, and expectations are established and people are given regular and constructive feedback. This sensemaking process is reinforced by work conditions that satisfy the personal motivation to demonstrate proself competence and autonomy and prosocial relatedness and conformity. People naturally want to use their skills, express their creativity, support each other, and fulfil their obligations.

Sensemaking and motivation are closely interrelated with culture and identity. Organizational culture provides an important source of sensemaking values and motivating identity. In particular, each person makes sense of a situation in relation to personal, relational, and group orientations to individual identity. For example, in terms of personal identity a job role affords the opportunity for an individual to satisfy their personal motivation to use their knowledge and skills. At the same time in terms of relational identity an individual is expected by others to fulfil their role responsibilities and most employees want to do this. Further, in terms of group identity individuals are naturally motivated to feel a psychological bond with their work group.

Effective leaders engage the whole person at work and appreciate the requirement to enable individuals to meet their needs to express and experience a motivating sense of personal, relational, and group identity. The motivating category of leadership practice is focused on the personal reasons that motivate individual action. In contrast the identity category of leadership practice is focused on an individual’s reflective awareness of themselves with associated emotional attachments and a sense of continuity through time.

Continuous learning is a natural outcome of the thoughts, feelings, and actions informed and energized by sensemaking and motivation. Consequently, a vital sensemaking skill is engaging people to reflect on what is going well and what could be done differently or better. This provides the foundation for ongoing adaptive learning and renewal.

POSITIVE RELATIONSHIPS DOMAIN: Culture & Identity Leadership Practices

We all have a natural motivation to identify with our work group and organization. This motivation is supported and reinforced by the sensemaking values and expectations that define the group.

Effective leaders promote and demonstrate the positive relationship practices associated with corporate culture and identity. Their success comes from contributing to their company’s culture and identity, gaining support for it throughout the business, including support for ongoing adjustments and change through time.

Use the statements below to review how frequently you observe these practices in your situation.

Culture: promote shared beliefs, values, & norms

- People push hard for competitive results

- People give detailed attention to monitoring operations

- People demonstrate high levels of mutual respect

- People are proactive in taking considered risks

Identity: promote group membership, attachment, and cohesion

- Individuals feel a bond with their work group

- Individuals identify with other members of their work group

Over time organizations develop their own distinctive corporate identity, a configuration of shared beliefs, values, and normative expectations and rules. On the one hand this configuration can involve more emphasis on a particular orientation, such as a competitive market orientation. On the other hand, higher levels of performance are associated with a practical emphasis on other orientations too. In general, this includes a systematic operational control orientation, a humanist mutual respect orientation, and an innovative risk taking orientation. Successful companies and leaders understand the dynamics of cultural values at organizational, functional, and work group levels, and promote a continuously evolving combination and balance across these different emphases. Within an organization, for example, the sales team is typically more market oriented, the production team is more operations oriented, the learning and development team is more humanist oriented, and the research and development team is more innovation oriented.

There is growing appreciation of the importance of identity in all aspects of human life. Crucially, individuals are strongly motivated to identify with an in-group. Indeed, this psychological bond is so strong that individuals give priority to in-group aims and values and can develop negative stereotypes about and actions towards out-groups and their members. Competition within companies between production and sales departments is an example of strong identification by individual members of sales and production teams with their respective in-group. Developing identification with superordinate corporate aims and values is essential for addressing these powerful natural forces in order to establish the conditions for constructive internal competition.

Constructive competition between work groups and within and between organizations is an important source of new ideas for competitive advantage. Therefore, the challenge is not to suppress group identification processes. The leadership challenge is to understand identification processes, especially group identification processes, and to develop and deploy that understanding to fulfil DEAR leadership responsibilities and realize relevant QBL outcomes.

Understanding and addressing the competitive processes that drive in-group perceptions, preferences, and priorities at the expense of an out-group is essential to meeting requirements relating to diversity, intercultural working, inclusion, and equality of opportunity and fair treatment. In-group identification processes can contribute to discrimination with respect to gender and ethnicity and can be a barrier to effective intercultural working. The social dynamics of individual identity are based on the way that individual mental processes operate and their effects on the interrelated processes associated with sensemaking, motivation, cultural beliefs and value orientations, and group identity. In particular, individual thoughts, feelings, and action are informed by a range of interconnected and culture dependent personal, relational, and group orientations to individual identity and its continuity and coherence through time.

Individuals want to belong to social groups that are distinctive and different, they want interpersonal and role relationships that enable them to contribute to their work group and organization, and they want to satisfy their personal prosocial motives for conformity and relatedness and their personal proself motives for competence and autonomy. Appreciation of the close interrelationships of motivation and identity can support leaders in creating high performance work groups and organizations. Similarly, sensemaking practices are infused with shared systems of meaning due to culture and identity processes and their associated practices.

A uniquely reflective awareness of individual identity has emerged from the group life of the human species and its socially constructed culture and institutional arrangements, including language. Hence, on the one hand, effective leaders appreciate the requirement to promote a shared sense of group identity and, on the other hand they appreciate the requirement to establish energizing reasons for action relevant to the unique talents, preferences, and aims and aspirations of each individual group member.

In combination goal setting and group relationship practices enable development of the team mental models that produce learning curve effects. Such learning can both drive costs down significantly and support continuous improvement and change. More generally, an understanding of how to deploy goal setting and positive relationship practices is vital for organization and culture change.

The leadership categories of sensemaking, motivation, culture, and identity and their specific practices can be adapted to situations when it matters to people to work together to achieve common aims. In all situations effective leadership is grounded in the sensemaking practices of establishing common aims and values and accepted ways of working, including feedback and reflection processes relevant to aims, values, ways of working, and outcomes. This requires high levels of skill in facilitating participative, negotiated, and emergent sensemaking and decision making throughout all aspects of working together on a joint agenda. These skills are enhanced by equally high levels of skill in promoting cultural beliefs, values, and norms that respect and energize personal, relational, and group orientations to individual identity.

COORDINATED ACTION DOMAIN: Collaboration & Decision Making Practices

Increasingly we all live, work, and interconnect on a global commons, which is evolving and changing rapidly. Coordinating and evolving information, decisions, and activities is challenging but essential if we are to continue to flourish and evolve a sustainable commons for an expanding population of over 7bn people.

Today’s successful leaders are masters of the interconnected coordinated action practices of collaboration and decision making.

Use the statements below to review how frequently you observe these practices in your situation.

Collaboration: enable people to work together to the same end

- Managers/team leaders plan carefully

- Managers/team leaders treat people fairly

- Managers/team leaders initiate new projects

Decision Making: involve people in decisions that affect them

- Managers/team leaders tell people what to do and explain the reasons

- Managers/team leaders seek input from people and this input influences decisions

- Managers/team leaders reach a mutually agreed decision with people following discussion

- Managers/team leaders enable decisions to emerge through trial and error action and discovery

Effective leaders provide task structure through effective planning, organization, and control. This includes establishing a division of labour and allocating and coordinating role responsibilities. Further, effective leaders promote positive relationships by showing consideration for others and treating people fairly. And, they enable adaptive change by initiating, promoting, encouraging, and supporting new ideas and new ways of doing things. These are examples of the practices associated with the broad task, relationship, and change dimensions of the collaboration category of leadership practice.

Task practices are vital for process control and relationship practices are vital for establishing trust and a positive sense of group identity. However, work group members may resist innovation and change. Crucially, trust is vital for engaging people in change. There is a dilemma here. Relentless pressure for cost control leads to tight process control. This can reduce scope for individuals to exercise initiative and discretion and may reduce scope to deploy and develop competence. This can reduce levels of trust and engagement and make it more difficult to engage employees in continuous adaptive learning and renewal. Higher levels of trust and positive group identity are essential for the engagement, alignment, and continuous learning and improvement that drive competitive performance and adaptive renewal.

The challenge for leaders is to deploy and develop all aspects of goal setting, positive relationship, and coordinated action leadership practices. In particular effective leaders establish motivating conditions for satisfying personal identity requirements to achieve proself competence and autonomy and prosocial relatedness and conformity. Moreover, effective leaders develop and promote cultural value and group identity orientations that reinforce energizing conditions for engagement and coordinated action. And throughout all aspects of motivation, culture, identity, and collaboration practices effective leaders are relentless in establishing shared goals, values, and expectations along with regular feedback, reflection, and progression of action plans that drive performance, continuous learning, improvement, and renewal.

An important aspect of employee engagement is the way employees are involved in decisions which affect them. Employees are motivated naturally to accept reasonable decisions by their manager or team leader, especially if reasons are explained. This is directive decision making and is associated with relatively tame problem solving situations. Participative decision making requires managers to seek input from direct reports in ways that are relevant to and which are seen to influence the decision taken. Participation helps to build trust and an open, humanist culture, and is associated with relatively tractable problem challenges.

Managers can engage in negotiation with peers or be involved in internal between group negotiations or external negotiations with a view to reaching a mutually agreed decision. These can be messy problem challenges and often negotiation skills are categorized as a specialist area of expertise rather than being associated with managerial leadership. However, group members in all contexts associate effective leadership with the skill of their manager in influencing laterally and upwards on behalf of group interests. In other words group members expect their team leader or manager to represent their personal and group related interests and priorities in competition with other groups on decisions about organizational aims and priorities and allocation of resources.

There is increasing recognition of the importance of adaptive leadership skills. This involves wicked decision challenges when there is an absence of agreement on both aims and values and on means to achieving aims. With such challenges an understanding of the situation and a decision can emerge as an outcome of trial and error action and discovery by group members. Sometimes it is only through such action that group members can explore, learn about and make sense of the situation they face. Through this sensemaking process group members come to recognize the presence of new priorities, goals, and values as an emergent outcome of their actions. Higher levels of trust and positive work group and organizational culture and identity support people in stepping into uncertainty and unknown unknowns to discover an emergent way forward through collaborative trial and error action and reflection.

In summary, in developing and deploying practices for fulfilling DEAR responsibilities in relation to QBL outcomes effective leaders implement the reflective learning and renewal activities integral to each of the six broad and interrelated categories of leadership practice. Furthermore, all aspects of leadership are informed by the general action processes of cooperative and competitive relationships in the implementation and innovation tasks of competitive performance and adaptive renewal.

3 General Action Processes for Survival and Identity

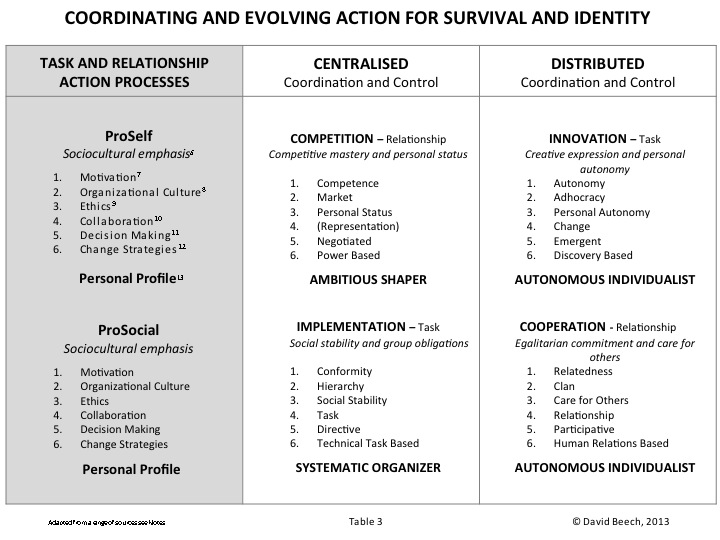

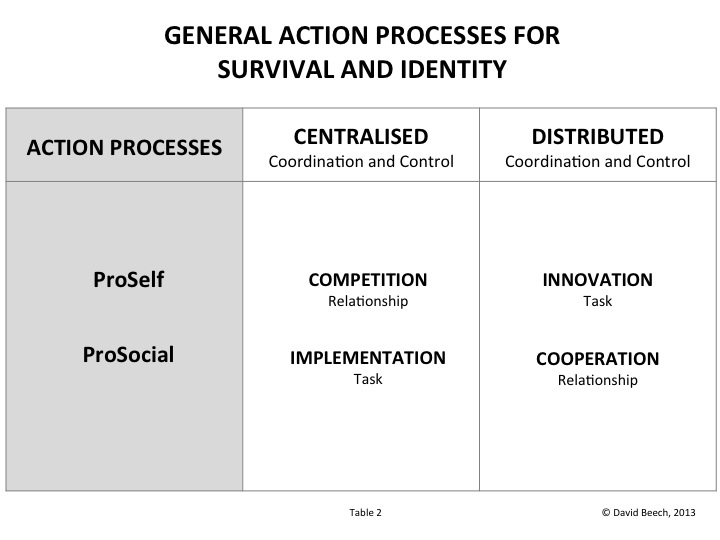

In our biocultural evolution there are recurring themes in how we get things gone for individual and community survival and identity. Evolving outcomes are produced through the intertwined action of cooperative and competitive relationship processes and implementation and innovation task processes. These dynamic, intertwined processes are simultaneously complementary and opposed. Further, at the most fundamental level of human existence from cells to civilizations, these four evolutionary action processes and their evolving effects are self organizing and subject to natural and cultural selection³.

A deeper understanding of leadership and higher levels of performance can be achieved by appreciation of how leadership practices are explained by the general action processes of cooperative and competitive relationships in the implementation and innovation tasks of engaging people in action for common aims and mutual benefits in evolving circumstances. These general action processes – see Table 2 and Table 3 below – are integral to all aspects of biological survival and sociocultural identity, including all aspects of QBL aims and outcomes, DEAR leadership responsibilities, and the six categories of leadership practice across the domains of goal setting, positive relationships, and coordinated action

Cooperative relationships enable people to work jointly to the same end and implementation puts a decision into effect to produce an outcome, for example to start a family or to build a supermarket. Hence, supportive cooperative relationships and task implementation goal attainment are fundamental for individual and community survival and identity. Decisive too is the innovation that produces the new variations and ways of working that accommodate to or that change circumstances. Moreover, evolution and success in the struggle for life requires competition between innovative ideas. However, competition that strives to achieve supremacy works against efforts to coordinate cooperative implementation. Thus a challenge for leaders is to enable a degree of constructive contention and self organized mutual adjustment among group members and between groups and to promote an adaptive learning culture in which people express different opinions in ways that are respectful of others.

The intertwined evolutionary processes of cooperative and competitive relationships in implementation and innovation tasks inform all aspects of the almost invisible dynamic processes of self organizing mutual adjustment and the more visible dynamics of leadership. Self organizing mutual adjustment within regulated markets is a complex mechanism for coordinating and evolving action for survival and identity. However, in this context it is important to recognize that unregulated cells are cancer cells that destroy their host. Regulation matters because similar toxic effects can develop when there is a lack of adequate regulation of competitive markets as demonstrated by the great crash of 1929 and the great recession of 2008. Nonetheless, it is clear that the creative competition of capitalism as far as possible within markets regulated as far as necessary drives sustainable prosperity. In addition, due to population pressure and resource depletion we need new concepts of the nature of growth and new institutional arrangements for governing growth in order to balance resource consumption with ecosystems sustainability in ways that meet individual and community requirements.

Unlike the spontaneous regulation of almost invisible self organizing biological processes all forms of organizing – in culture dependent social networks, self governing associations, markets, and hierarchical organizations – are subject to reflective regulation by the human groups that construct them. Leadership matters because it is a fundamental mechanism for coordinating and evolving reflective regulation of general action processes and effects. Leaders enable individuals to work together to produce results they could not produce by working on their own. Furthermore, in relation to all forms of organizing, group members establish innovative institutional arrangements like money, property rights, employment contracts, and limited liability companies. Cumulative innovations in institutional arrangements transform the scale and scope of the capacity to work together for common aims and mutual benefits. A natural willingness to conform to road traffic law, for example, enables millions of people to implement daily motorized transport activities in pursuit of their individual aims and preferences. In general, self organizing mutual adjustment, leadership, and socially constructed institutional arrangements are three fundamental and interrelated mechanisms for coordinating and evolving action for survival and identity⁴.

The general action processes of evolution and natural selection inform all aspects of group living and leadership practices in the struggle for life. For example, the structure of human motives for proself competence and autonomy and prosocial relatedness and conformity has evolved from the intertwined and cumulative effects of biocultural requirements for centralised and distributed coordination and control of action processes and intertwined biocultural requirements for an independent proself orientation and an interdependent prosocial orientation to personal identity. Moreover, the underlying structure of cultural values and personal motives is the same across all nations, organizations, work groups, and individuals⁵. However, consistent with evolutionary theory it is essential to recognize that the ‘DNA’ of general action processes generates an infinite variety of activities and outcomes. Thus, there are wide variations in culture dependent patterns of behaviour within and between societal communities such as China, India, and the USA; and, for example, there are huge differences between competition as a ‘win-lose’ zero sum power over others process and competition as a ‘win-win’ power with others process. More generally, a range of robust and practical findings relevant to the leadership practices of goal setting, positive relationships, and coordinated action can be explained in relation to four intertwined general action processes.

All aspects of leadership across the practice categories of motivation, culture, collaboration, and decision making are based on the intertwined, complementary and opposing dynamics of cooperative and competitive relationship and implementation and innovation action processes. See Table 3 below. Further, with respect to coordinating and evolving action for individual survival and reproduction of a way of life individual and group understanding of situations – sensemaking – is informed by the combined operation of the four action processes. At the same time these action processes inform the expression and experience of culture dependent individual identity and meaning. In other words, the four action processes generate all aspects of goal setting, positive relationships, and coordinated action in fulfilling DEAR responsibilities and realizing QBL outcomes.

In addition, and fundamentally, human action is informed by ethical requirements. For example, requirements for ethically legitimate enterprise, transparency, and accountability define the responsibilities of corporate governance. From a broad perspective the fundamental ethical dilemmas of the group living human species are ethical moral and ethical political dilemmas. The moral dilemma is how to balance preferences for personal status and competitive success with preferences to care for and to trust others. The political dilemma is how to balance preferences for personal autonomy and freedom with preferences for social stability and order.

From the perspective of four intertwined general action processes and their evolving effects ethics is a natural development of the evolution of cooperative and competitive relationship activities throughout all aspects of implementation and innovation task activities. Ethics is the basis for regulation of the actions of group living individuals and artificial persons such as corporations. Accordingly, attention to ethics is a fundamental requirement across all levels of leadership, with particular significance at the highest institutional level which sets the agenda for QBL aims and outcomes and for the leadership practices through which DEAR responsibilities are fulfilled by strategic, operational, and frontline leaders.

In terms of the ethical dynamics of creative competition the recent Manifesto for a Global Economic Ethic¹⁴ acknowledges the requirement to balance self interest and concern for others, stating, “Self-interest and competition serve the development of the productive capacity and the welfare of everyone involved in economic activity. Therefore, mutual respect, reasonable coordination of interests, and the will to conciliate and to show consideration must prevail.” Thus the ethical requirements of the Manifesto are consistent with the vital contribution of leadership practices to creative competition as far as possible and cooperative regulation as far as necessary.

Change is an evolutionary constant. Leading change for adaptive learning and renewal is a fundamental day to day leadership responsibility. Adaptive learning and renewal is embedded in the fabric of individual and corporate action and is integral to all aspects of goal setting, positive relationships, and coordinated action. The more that leaders develop and deploy the understanding and skills associated with sensemaking, motivation, culture, identity, collaboration, and decision making leadership practices the more they are equipped with the capacity to enable change. The introduction of new technology and new ways of working can often be achieved through technical task based change and directive leadership supported by participative human relations involvement of group members in arrangements for how change will be implemented, including education and training. However, the more that change has an impact on an individual’s work relationships and, in particular on their culture dependent sense of individual identity and associated cultural value orientations the more there is a requirement for power and discovery based strategies for change.

Fulfilling DEAR responsibilities in realizing a variety of QBL aims and outcomes is a compelling challenge requiring the highest levels of skill in implementing interrelated goal setting, positive relationship, and coordinated action practices. This briefing provides practical checklists – brought together in Appendix One – against which to review leadership activities in your own situation. Further, a deeper understanding and higher levels of performance can be achieved by appreciation of how leadership practices are explained by the general action processes of cooperative and competitive relationships in the implementation and innovation tasks of engaging people in action for common aims and mutual benefits in evolving circumstances. A deeper level of understanding is essential for leading organization and culture change in today’s tough and turbulent conditions.

Managerial leadership matters because managerial leaders everywhere sit in the front seat of history. Through our work with groups and group members each day we reproduce and cumulatively transform the conditions of life for people, profit, planet, and progress. The checklists above provide evidence based examples of how to contribute to the compelling challenge of providing effective leadership for competitive performance and adaptive renewal. Crucially, in fulfilling DEAR responsibilities the most effective leaders integrate reflective learning and renewal activities relevant to each category of leadership practice.

For more information visit www.cambridgeleadershipdevelopment.com or contact Angela Sherrington at asherrington@camlead.com

Acknowledgements

The materials presented in this briefing have been created in response to the leadership and organization development requirements of over 1,500 senior executives and middle managers in mostly global Fortune 500 companies, over a 15 year period. I am grateful to them for their involvement and stimulation.

I would like to thank the School of Psychology, University of Sussex for their continuous support since 2000 for the research that informs this executive briefing. I also appreciate the opportunity enabled by Professor John Burgoyne to present an earlier version of this briefing at Lancaster University Management School in December 2012.

About the author

David Beech

Co-founder, Director of Learning and Development

DPhil, CPsychol, AFBPsS

David co-founded Cambridge Leadership Development and is the Director of Learning and Development. He specialises in leadership and organization development, his focus is designing, developing and delivering a broad spectrum of customised and open leadership and management development programmes, for a wide range of clients.

David has worked across industries and engagements throughout Europe, the US, and Asia. Current and recent clients include Bayer, Saint-Gobain, BBC, Glaxo-Wellcome, Ecolab, EMLYON Business School, Novartis, NHS, Cranfield School of Management, L’Oreal and Oracle.

Prior to founding Cambridge Leadership Development in 2003, David was Client and Programme Director for Leadership and Organization Behaviour at Ashridge Business School, where he was a main contributor to the design, development and delivery of the Ashridge Leadership Process; as Principal Consultant in Organizational Effectiveness at Hewitt Associates, he focused on culture change projects in Europe and the USA; and at SHL, he designed and delivered Assessment and Development Centres for all levels of management from the boardroom to the frontline. David held managerial and executive roles in Organization Development and HR Management with Unilever, Siemens, Duracell, and Nashua. He has 25 years international experience.

He holds a DPhil in Social Psychology from the University of Sussex, an MSc in Organizational Behaviour from the University of London, and a BSc in Philosophy, Psychology and Sociology, and is an organizational psychologist.

David is an Associate Fellow of the British Psychological Society, and a qualified psychometric assessor in a range of tools, including OPQ, 16PF, California Personality Inventory, Myers Briggs, FIRO-B, TMSDI team profiling, Belbin, and CCL’s Benchmarks 360.

Notes

A selective list of sources for leadership research findings.

- See Yukl, G. 2010. Leadership in Organizations, 7th ed. New York: Pearson; and Bass, B.M. 2008. The Bass Handbook of Leadership, 4th ed. New York: Free Press for general reviews of leadership research findings and note 2 below for research relevant to the six categories of leadership practice. Identification of DEAR leadership responsibilities (leadership functions) is a development of the seminal research of R. Freed Bales and Talcott Parsons. See Parsons, T., Bales, R.F., & Shils, E.A. (1953). Working papers in the theory of action. New York: Free Press. See Beech, D. 2013. QBL: A quadruple bottom line for sustainable prosperity. Cambridge Leadership Development Executive Briefing No. 1 for further details.

- For findings relevant to sensemaking see Smith, P.B. & Peterson, M.F. 1988. Leadership, organizations, and culture. London: Sage. For motivation see Deci, E.L. & Ryan, R.M. 2012. Self-Determination Theory. Chapter 20 in P.A.M. Van Lange, A.W. Kruglanski, & E.T. Higgins (Eds.) Handbook of theories in social psychology. Vol. 1. Los Angeles: Sage; and Prislin, R. & Crano, W.D. 2012. A history of social influence research. Chapter 15 in A.W. Kruglanski & W. Stroebe (Eds.) Handbook of the history of social psychology. New York: Psychology Press. For culture see Cameron, K.S. & Quinn, R.E. 2011. Diagnosing and changing organizational culture, 3rd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. For identity see Schwartz, S.J., Luyckx, K., & Vignoles, V.L. 2011. Handbook of Identity Theory and Research, Vols 1 & 2. New York: Springer. For collaboration see Yukl, G. 2012. Effective leadership: What we know and what questions need more attention. Academy of Management Perspectives, Nov 66-85. For decision making see: Thompson, J.D. & Tuden, A. 1959. Strategies, structures, and processes of organizational decision. Chapter 12 in J.D. Thompson et al. (Eds.) Comparative studies in administration. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press; Stacey, R.D. 1996. Strategic management and organizational dynamics, 2nd ed. London: Pittman; and, Snowden, D.J. & Boone, M.E. 2007. A leader’s framework for decision making. Harvard Business Review, 85, 68-76.

- See Parsons, T., Bales, R.F., & Shils, E.A. (1953). Working papers in the theory of action. New York: Free Press. Bales identified four group level functions of leadership: task goal attainment, task adaptation, relationship integration and relationship emotional tensions management. These are equivalent respectively to the general action processes of implementation and innovation task activities and cooperation relationship activities. Emotional tensions management is the leadership response to competition and conflict in the group. Generally, these functions are simplified into a contrast between two leadership roles: task specialist and socioemotional specialist. Due to this Bales’ distinction between task implementation and task innovation functions is neglected. In addition, while Parsons, Bales, and Shils recognised the presence of competition they focused attention on the cooperative function of resolving tension due to competition. Thus, they did not identify competition as one of four general action processes. The original synthesis presented in this executive briefing builds on the work of Parsons and his colleagues.

- See Mintzberg, H. 1979. The structuring of organizations. London: Prentice-Hall. Mintzberg identifies mutual adjustment, direct supervision and standardization of work, outputs, and skills as coordinating mechanisms. Standardization requires institutional arrangements, for example a division of labour, distribution of role responsibilities, and exchange relationships with associated normative expectations, rules and regulations.

- See Schwartz, S.H. 2011. Values: cultural and individual. Chapter 18 in F.J.R. van de Vijver, A. Chasiotis, & S.M. Breugelmans (Eds.) Fundamental questions in cross-cultural psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; and, Fischer, R. & Poortinga, Y.P. 2012. Are cultural values the same as the values of individuals? An examination of similarities in personal, social, and cultural value structures. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 12, 157-170.

- Adapted from a range of sources, including in particular Schwartz; see note 5 above.

- See the references for motivation in note 2 above.

- See the reference for culture in note 2 above.

- See Norman, R. 1998. The moral philosophers: An introduction to ethics, 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; and Wolff, J. 2006. An introduction to political philosophy, Rev Ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- See the reference for collaboration in note 2 above.

- See the references for decision making in note 2 above. In addition see Rittel, H. & Webber, M. 1973. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4, 155-169.

- See Chin, R. & Benne, K.D. 1984. General strategies for effecting changes in human systems. Chapter 1.2 in W.G. Bennis, K.D. Benne, & R. Chin (Eds.) The planning of change, 4th ed. Fort Worth, TX: Holt, Rinehart & Winston; and, Thurley, K. & Wirdenius, H. 1989. Towards European Management. London: Pitman.

- Source: Beech, D. 2013. Derived from personality and team roles research, e.g., Belbin, R.M. 1981. Management Teams. London: Heinemann.

- Kung, H., Leisinger, K.M., & Wieland, J. 2010. Manifesto [for a] Global Economic Ethic. Munich: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag.

Appendix One: LEADERSHIP PRACTICES

The checklist below defines each category of leadership practice and provides examples of practices and outcomes. Use the following scoring system to describe how frequently you observe these practices in your situation:

- Never/rarely

- Sometimes

- Many times/frequently

- Most of the time

- Almost always/always

About Cambridge Leadership Development

We are a specialist leadership development company. Cambridge Leadership Development combines deep specialist expertise and knowledge in leadership and development with broad industry experience.

We work in true partnership with our clients to develop existing and emerging leaders at every level, to improve effectiveness and performance, for organizational and individual success.

We are passionate about developing the leaders our clients need to compete successfully in today’s fiercely competitive business environment that changes round the clock, around the world.

Cambridge Leadership Development design, develop and deliver leadership and development solutions and services that develop the leaders each client needs to compete and grow.

Our Approach

Our approach is practically focused and connects business strategy with daily work. We offer a broad range of leadership and development services, including experiential programmes and workshops, client specific action learning projects, development centres and processes, competency frameworks and 360s, and coaching.

For more information about how Cambridge Leadership Development can help your business, please contact:

Angela Sherrington +44 (0) 1945 429 278 asherrington@camlead.com